Mystical Tenochtitlan: Sacred Citadel of the Aztec Spiritual World

Tenochtitlan: Unveiling the Mystic Traditions and Engineering Marvels of the Aztec Metropolis

Key Takeaways

The island city of Tenochtitlan was a marvel of urban planning, engineering, and architectural prowess, showcasing the Aztecs' ingenuity and adaptability to their lacustrine environment.

Tenochtitlan's design, layout, and ceremonial structures were imbued with profound symbolic and spiritual significance, reflecting the Aztecs' intricate belief system and their reverence for the cosmic order.

The 1524 map of Tenochtitlan serves as a syncretic masterpiece, blending indigenous and colonial perspectives, offering a unique glimpse into the grandeur of the Aztec capital.

The city's chinampas (floating gardens) and sophisticated water management systems exemplified the Aztecs' deep ecological awareness and sustainable relationship with their environment.

Despite its eventual destruction, Tenochtitlan's legacy endures, etched into the cultural fabric of Mexico, and serving as a testament to the resilience of indigenous civilizations in the face of conquest.

Mystical Tenochtitlan: Sacred Citadel of the Aztec Spiritual World

Rising from the shimmering waters of Lake Texcoco like a resplendent mirage, the island city of Tenochtitlan stood as the crowning glory of the Aztec Empire. This "Venice of the New World," as it was aptly dubbed by the earliest Spanish conquistadors (Díaz del Castillo, 1908), embodied the profound architectural, engineering, and cultural achievements of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

Today, over five centuries since its fall, the legacy of Tenochtitlan endures, etched into the historical and cultural fabric of Mexico through remnants of its grandiose structures, urban planning marvels, and the indelible imprint it left on the valley's topography. At the heart of this legacy lies the 1524 map – the first European depiction of the Aztec capital, a syncretic masterpiece that serves as a poignant confluence of indigenous and colonial perspectives.

Aztec Princess Poses with Native Wildflowers

Origins and Rise of the Aztec Civilization

To comprehend the magnificence of Tenochtitlan, one must first delve into the origins and meteoric rise of the Aztec civilization. According to their founding myth, the Aztecs, or Mexica as they called themselves, were a nomadic tribe from the mythical homeland of Aztlán (León-Portilla, 1962). Guided by their principal deity, Huitzilopochtli, they embarked on a centuries-long journey, seeking the prophesied sign that would mark their promised land: an eagle devouring a serpent while perched on a prickly pear cactus.

In 1325 CE, the wandering Mexica purportedly witnessed this symbolic portent on a small island in Lake Texcoco, nestled within the Valley of Mexico (Townsend, 2000). Heeding the divine directive, they established their settlement, Tenochtitlan, on this seemingly inhospitable terrain. Through sheer tenacity and an ingenious system of chinampas (floating gardens), the Aztecs transformed the lacustrine landscape into a fertile oasis, laying the foundation for their burgeoning empire (Calnek, 1972).

The Great Tlatoani of the Aztec Empire, Surreal Vapor Dream

The Great Tlatoani's Procession

As the first rays of dawn pierce the morning mist, the hushed streets of Tenochtitlan stir to life. From the ceremonial precinct, a procession emerges, led by the Great Tlatoani himself, resplendent in his regalia of jade and quetzal feathers. He is borne aloft on an elaborate litter, flanked by ranks of elite warriors adorned in the fearsome accouterments of the Jaguar and Eagle knights.

The rhythmic beat of ceremonial drums reverberates through the island city as the cortege winds its way along the canals. Incense wafts through the air, mingling with the heady aroma of fresh marigolds that carpet the procession's path. Awestruck onlookers gather along the waterways, jostling for a glimpse of their revered ruler as he journeys to the sacred Templo Mayor.

At the foot of the towering pyramid, a line of priests in loincloths await, their bodies painted in ritualistic patterns. The Tlatoani ascends the steep steps, his retinue fanning out behind him like a living tapestry of feathers and jade. As he reaches the summit, the first rays of the rising sun catch the gleam of the sacrificial blade, and the air is rent with the piercing cry of a captive warrior.

Mystical Tenochtitlan, Ancient Aquatic Capital of the Aztec Empire

The Cosmic Order: Aztec Spirituality and Its Manifestation in Tenochtitlan

At the heart of Tenochtitlan's grandeur lay a profound spiritual cosmology that permeated every aspect of Aztec civilization. The island city was not merely a political and economic center; it was a living embodiment of the Aztecs' intricate belief system, a microcosm that mirrored the celestial order of the universe itself (León-Portilla, 1963). To comprehend the symbolic significance and mystical undertones woven into Tenochtitlan's very fabric, one must delve into the rich tapestry of Aztec spirituality and its inextricable link to the natural world.

Hypnotic Gaze of the Aztec Shamanic Elder

The Cyclical Nature of Time and Existence

Central to Aztec thought was the concept of a cyclical, ever-renewing universe governed by the perpetual motion of cosmic forces (Matos Moctezuma, 1988). This belief manifested itself in their unique conception of time, which was measured not in linear progression but rather in great cycles punctuated by periodic cataclysms and renewals. The Aztecs saw themselves as participants in the present, fifth iteration of the world, which they called Nahui-Ollin, or the "Sun of Movement" (Townsend, 2009).

This cyclical worldview was intrinsically tied to the rhythms of nature, particularly the celestial movements of the sun, moon, and planets. The Aztec calendar system, a masterwork of astronomical observation and mathematical precision, reflected this deep reverence for cosmic patterns. The Xiuhpohualli, or solar calendar, tracked the annual cycle of the sun's path, while the Tonalpohualli, or sacred calendar, encompassed a 260-day cycle that governed religious rituals and divination practices (Aveni, 2001).

Aztec Princess Poses with Native Wildflowers

The Symbiosis of Tenochtitlan and the Cosmos

Tenochtitlan's very layout and architectural design were carefully orchestrated to mirror this cosmic order, creating a sacred space that bridged the terrestrial and celestial realms. The city's iconic Templo Mayor, dedicated to the dual deities Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, was a symbolic representation of the duality that governed the Aztec universe (Carrasco, 1999).

The pyramid's eastern face, adorned with vibrant carvings of Tonatiuh, the sun deity, paid homage to the life-giving solar forces that sustained the world. Conversely, the western façade was dedicated to Tlaloc, the rain god, whose dominion over water and fertility was crucial to the existence of the island city (Townsend, 2009). This deliberate alignment of the sacred edifice with the celestial bodies not only underscored the Aztecs' reverence for the cosmos but also ensured that the temple's ceremonies and rituals were precisely calibrated to the rhythms of the heavens.

Beyond the Templo Mayor, the very orientation of Tenochtitlan's causeways and canals was meticulously planned to align with astronomical events, such as the rising and setting of the sun during the equinoxes and solstices (Šprajc & Sánchez, 2012). This cosmic resonance extended to the city's residential zones, where households were arranged according to specific calendrical and astrological associations, creating a harmonious tapestry of sacred symbolism and practical urban planning.

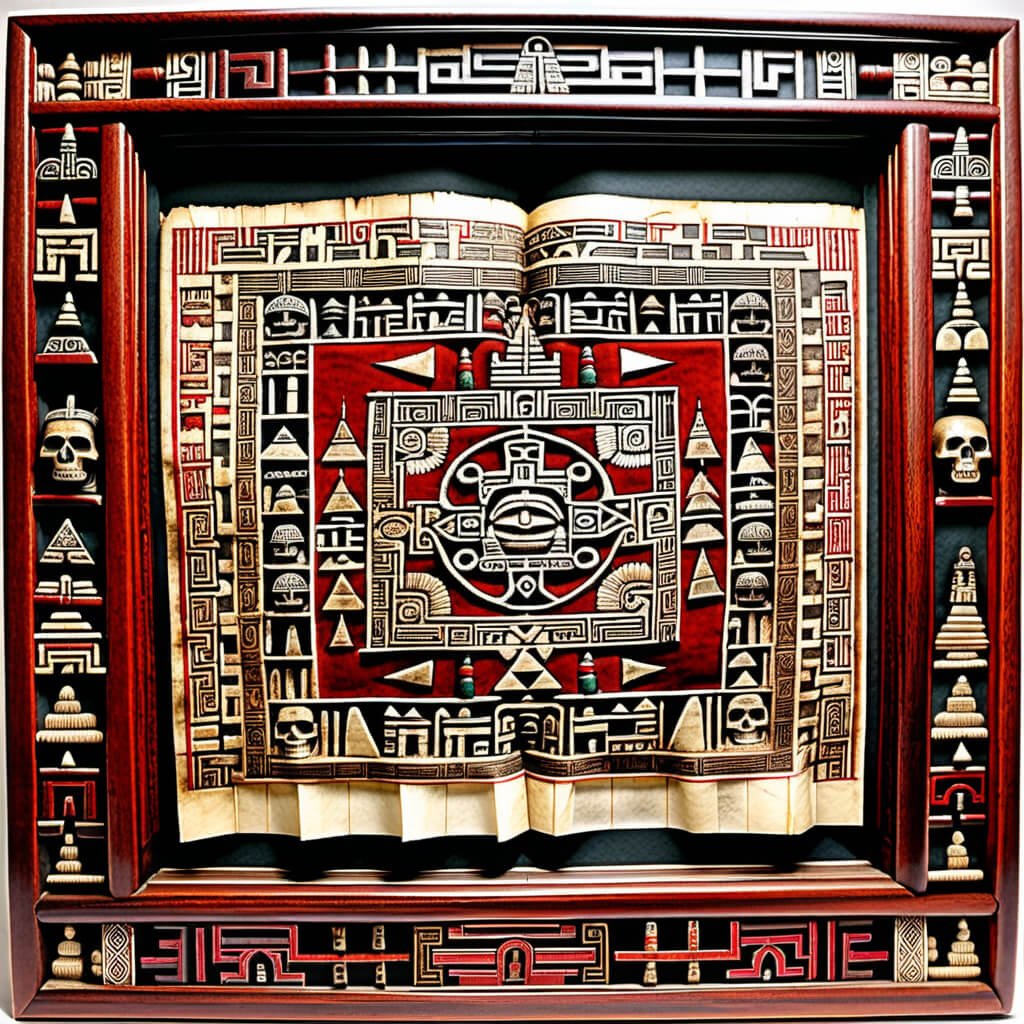

Blood of the Gods, Ancient Aztec Text Outlines Ritual Calendar of Tenochtitlan

The Blood of the Gods: Ritual Sacrifice and Renewal

Perhaps the most striking manifestation of Aztec spirituality was the practice of ritual sacrifice, which played a central role in the religious and social fabric of Tenochtitlan. Far from being acts of mere bloodlust, these rituals were rooted in a profound belief in the cyclical nature of existence and the need to nourish the cosmic forces that sustained life itself (Carrasco, 1999).

According to Aztec mythology, the present era of the world was born from the self-sacrifice of the gods, who offered their blood to give life to the sun and ensure the perpetuation of the cosmic cycle (Townsend, 2009). Human sacrifice, then, was seen as a sacred duty, a means of repaying the debt owed to the deities and ensuring the continued flourishing of the universe.

The Templo Mayor, with its twin shrines to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, served as the epicenter of these rituals, where captive warriors and willing participants were sacrificed in elaborate ceremonies. The ancient chronicles vividly depict the pageantry of these events, with processions of richly adorned priests and nobles converging on the sacred precinct, accompanied by the rhythmic beat of drums and the pungent aroma of copal incense (Sahagún, 1950-1982).

Yet the practice of sacrifice extended far beyond the bounds of the Templo Mayor. Throughout Tenochtitlan, smaller temples and shrines dotted the landscape, each dedicated to a specific aspect of the Aztec pantheon and serving as a locus for rituals and offerings (Smith, 2003). The city's very infrastructure facilitated these sacred observances, with canals and causeways providing ceremonial routes for processions and the transportation of ritual materials.

Mystical Waterways of the Ancient Aztec Capital Tenochtitlan

The Reverence for Nature and Its Embodiment in Urban Design

Underpinning the Aztecs' spiritual beliefs was a profound reverence for the natural world and its myriad forces. The Aztec pantheon was populated by deities that personified the elements – fire, water, earth, and air – as well as the celestial bodies and natural phenomena that governed the cycles of life (Matos Moctezuma, 1988). This deep connection to nature manifested itself in Tenochtitlan's ingenious urban planning and environmental management strategies.

The chinampas, or floating gardens, that dotted the lacustrine landscape surrounding the city were not merely feats of agricultural ingenuity; they were living embodiments of the Aztecs' symbiotic relationship with their environment (Coe, 1964). By intentionally flooding and cultivating these artificial islands, the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan were engaging in a sacred act of renewal, mirroring the cyclical patterns of inundation and fertility that sustained the ecosystem of the Valley of Mexico (Armillas, 1971).

Moreover, the city's sophisticated water management systems, with their intricate dams, sluice gates, and aqueducts, were designed not only to provide fresh water and control flooding but also to honor the sacred waters that nourished the land. The very canals that crisscrossed Tenochtitlan were imbued with spiritual significance, serving as ceremonial routes for rituals and offerings to the water deities (Palerm, 1973).

Aztec Jaguar Shaman Poses Wearing a Cermonial Jaguar Skin Mask

The Enduring Legacy: Aztec Spirituality in Modern Mexico

While the physical manifestations of Aztec civilization were largely obliterated by the Spanish conquest, the spiritual and mystical foundations that shaped Tenochtitlan continue to echo through the cultural and religious traditions of modern Mexico. The syncretic blend of indigenous and Catholic beliefs that emerged in the wake of colonization bears the indelible imprint of Aztec cosmology, with rituals and celebrations honoring the cyclical patterns of nature and the forces that govern the universe (Carrasco, 1999).

Festivals such as Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) and the various celebrations surrounding the spring and fall equinoxes are rooted in pre-Hispanic traditions that venerated the cyclical nature of existence and the perpetual renewal of life (Brundage, 1979). Even the architecture of colonial-era churches and cathedrals, many of which were built atop the ruins of Aztec temples, reflects a subtle fusion of indigenous and European symbolism, with celestial alignments and natural motifs subtly woven into their design (Kubler, 1948).

In the end, the mystical and spiritual underpinnings that guided the construction and daily life of Tenochtitlan represent a profound testament to the Aztecs' deep reverence for the cosmos and their place within the natural order. By studying the symbolic significance and esoteric beliefs that permeated every aspect of the island city, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of human spirituality and the enduring legacy of a civilization that sought to harmonize the terrestrial and celestial realms.

Mystical Spirit of the Aztecs, Surreal Vapor Dream

The Grandeur of Tenochtitlan: An Engineering Marvel

As the Aztec empire expanded, subsuming neighboring city-states through conquest or alliance, Tenochtitlan grew in tandem, evolving into a metropolis of unprecedented scale and sophistication. The 1524 map, meticulously crafted by indigenous artists and scribes under Spanish oversight (Mundy, 1996), offers a captivating glimpse into the city's intricate layout, replete with awe-inspiring architectural and engineering feats.

At the heart of the map lies the ceremonial precinct, dominated by the imposing Templo Mayor, a stepped pyramid adorned with serpentine carvings and the skulls of sacrificial victims. This sacred edifice served as the spiritual nucleus of Tenochtitlan, a testament to the inextricable link between religion, power, and the Aztec worldview (Carrasco, 2000). Surrounding the Templo Mayor was an intricate network of canals, resembling the fabled canals of Venice, that facilitated transportation and trade within the island city.

One of the most remarkable achievements depicted on the map is the series of causeways that connected Tenochtitlan to the mainland. These elevated roads, constructed atop a layer of woven reeds and earth, spanned several kilometers across the lake, allowing for the flow of goods, people, and freshwater from the mainland aqueducts (Rojas, 1986). The causeway system was further fortified by strategic military outposts, underscoring the Aztecs' prowess in defensive architecture.

Aztec War Party, Surreal Vaporwave Watercolor

The Chinampas of Xochimilco

Beyond the bustling heart of Tenochtitlan, the tranquil waters of Xochimilco reveal a different facet of the Aztec capital's ingenuity. Here, a vast network of chinampas, or floating gardens, stretches as far as the eye can see, their verdant expanse crisscrossed by narrow canals teeming with canoe traffic.

On one such chinampa, a family tends to their precious crops, their hands calloused from years of labor in the fertile soil. A young boy deftly navigates a shallow canal, using a long pole to propel his canoe laden with freshly harvested vegetables and fragrant flowers.

Nearby, an elderly woman pauses to wipe the sweat from her brow, surveying the intricate lattice of ahuejotes – the willow trees whose interwoven roots form the very foundation of these floating gardens. She murmurs a prayer of gratitude to Xipe Totec, the Aztec deity of agriculture, as she recalls the ingenuity of her ancestors who transformed this once-barren lakebed into a verdant breadbasket.

As the day wanes, the chinampas take on an ethereal quality, the setting sun casting a warm glow over the rippling waters and the lush greenery. It is a scene that has endured for generations, a testament to the Aztecs' profound connection to their land and water, and their ability to shape even the most inhospitable of environments into a sustainable oasis.

Spirit Fire of the Aztec Nation, Shamanic Priestess

Water Management and Urban Planning

Beyond its physical grandeur, Tenochtitlan's true marvel lay in its sophisticated water management and urban planning systems. The map vividly illustrates the city's division into four quadrants, each with its own specialization and administrative hierarchy (Aguilar-Moreno, 2006). This systematic organization facilitated efficient governance and resource distribution, a remarkable feat for a metropolis of its size.

At the core of Tenochtitlan's water management prowess was the intricate system of dams and sluice gates that regulated the flow of water from the surrounding lakes (Palerm, 1973). This engineering marvel not only provided fresh water for the city's residents but also served as a formidable defense mechanism, allowing the Aztecs to control the depth of the surrounding waters and impede enemy advances.

The map also reveals the ingenious concept of chinampas – artificial islands constructed from interwoven reeds and fertile soil dredged from the lake bed (Coe, 1964). These floating gardens not only supplied the city with a bountiful array of agricultural produce but also acted as a natural filtration system, enhancing the water quality and mitigating the effects of periodic flooding.

Aztec War Parties Gather at Tenochtitlan, Surreal Vaporwave Watercolor

Symbolic Significance and Artistic Representation

Tenochtitlan's grandeur extended far beyond its physical manifestations; it was imbued with a profound symbolic and artistic significance that permeated every aspect of Aztec culture. The 1524 map itself is a remarkable fusion of European and indigenous artistic traditions, blending the bird's-eye perspective of European cartography with the vibrant colors, glyphs, and symbolic representations characteristic of Aztec codices (Robertson, 1994).

One of the most striking features of the map is the depiction of the city's iconic twin pyramids, the Templo Mayor and the Tzompantli (skull rack). These structures served as potent symbols of the Aztecs' militaristic might and their intricate religious rituals, which often involved human sacrifice (Townsend, 2000). The map's vivid portrayal of these edifices not only captured their architectural splendor but also hinted at the complex spiritual and philosophical underpinnings of Aztec society.

Moreover, the map's inclusion of richly illustrated scenes of daily life, such as the bustling marketplace of Tlatelolco and the vibrant canoe traffic on the canals, offers a tantalizing glimpse into the cultural vibrancy and economic dynamism that characterized Tenochtitlan (Berdan, 1976). These depictions underscore the city's status as a cosmopolitan hub, where trade, art, and indigenous knowledge flourished.

Shamanic Jaguar Priestess of the Ancient Aztec Empire

Ecological and Environmental Adaptations

Tenochtitlan's remarkable development was intricately intertwined with its unique lacustrine environment. The Aztecs' ability to adapt to and harness the resources of the Valley of Mexico's lake system was a testament to their profound ecological awareness and ingenuity.

Through the construction of the chinampas, the Aztecs not only created a sustainable agricultural system but also demonstrated a deep understanding of the intricate hydrological cycles and nutrient flows within the lake ecosystem (Armillas, 1971). By intentionally flooding the carefully constructed reed beds with nutrient-rich waters from the surrounding lakes, they created a self-sustaining, highly productive agricultural system that supported the burgeoning population of Tenochtitlan.

Furthermore, the Aztecs' management of water resources extended beyond the confines of the city itself. The construction of elaborate aqueduct systems, such as the one depicted in the 1524 map, allowed for the transportation of fresh water from distant springs and rivers, ensuring a reliable water supply for the capital (Sanders, 1976). These engineering marvels not only showcased the Aztecs' technical prowess but also highlighted their ability to adapt to and sustainably shape their environment.

Sprawling Temple Complexes of the Ancient Aztec Citadel Tenochtitlan

Clash of Civilizations: The Fall of Tenochtitlan

Tragically, the very map that celebrated Tenochtitlan's grandeur also foreshadowed its eventual demise. In 1521, after a prolonged siege and fierce resistance, the Aztec capital fell to the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his allied indigenous forces (Díaz del Castillo, 1908). The once-mighty city was reduced to rubble, its magnificent structures razed to the ground, and its inhabitants decimated by violence and disease.

The juxtaposition of the 1524 map's vibrant depiction of Tenochtitlan and the accounts of its harrowing destruction by Spanish chroniclers is a poignant reminder of the profound cultural clash that occurred during the conquest of the Americas. As the conquistadors marveled at the city's splendor, they simultaneously sought to erase its indigenous roots, imposing their own religious and architectural paradigms on the conquered land (Muñoz Camargo, 1892).

Indigenous Mexican Woman Poses Wearing Traditional Aztec Ceremonial Costume

First Encounters

The morning mists still clung to the placid waters of Lake Texcoco when the first strange vessels appeared on the horizon. From his vantage point on the shores of Tenochtitlan, a young Aztec warrior tensed, gripping his obsidian-edged macuahuitl as the bizarre floating structures drew ever closer.

Never before had he laid eyes upon such peculiar crafts, their pale, billowing sheets catching the fickle lake breezes. Nor had he ever witnessed creatures as outlandish as the beings that occupied them – men with sun-bronzed skin and faces obscured by thick hair.

As the ships approached the great city's causeways, a contingent of Aztec warriors assembled, their bodies adorned with fearsome regalia as they braced for an attack from these unknown invaders. But the strange men made no hostile advances. Instead, they seemed to gaze upon the magnificent island capital in awe and disbelief.

From his flagship, the bearded commander known as Hernán Cortés could scarcely comprehend the majesty of Tenochtitlan. The city's soaring pyramids and the vast expanse of its orderly causeways and canals were like nothing he had ever encountered. As his men murmured anxiously, questioning whether they had indeed stumbled upon one of the fabled cities of gold, Cortés felt a surge of anticipation – and trepidation – course through his veins. For in that moment, two vastly disparate worlds had collided, setting the stage for an epochal clash of civilizations that would forever alter the course of history.

Reclaiming the Mystic Heritage of the Ancient Aztec Empire

Remnants and Rediscovery: Tenochtitlan's Enduring Legacy

Despite the physical obliteration of Tenochtitlan, its legacy persisted, woven into the fabric of modern-day Mexico City. The colonial city was built atop the ruins of the Aztec capital, its streets, and plazas echoing the layout depicted in the 1524 map (Calnek, 1976). Archaeological excavations, particularly those led by Manuel Gamio and Eduardo Matos Moctezuma at the Templo Mayor site, have unearthed remnants of the Templo Mayor, the Tzompantli, and other monumental structures, providing tangible links to the city's pre-Hispanic past (León-Portilla, 1987).

Moreover, Tenochtitlan's influence can be traced to the artistic, culinary, and linguistic traditions that endure within Mexican culture. From the vibrant murals adorning public spaces to the rich tapestry of indigenous languages still spoken today, the echoes of the Aztec capital reverberate through the nation's contemporary identity (Lara, 2008).

In recent decades, there has been a concerted effort to recognize and celebrate Tenochtitlan's legacy, both within Mexico and internationally. The creation of museums and cultural centers, such as the Museo del Templo Mayor and the Museo Nacional de Antropología, have played a pivotal role in preserving and disseminating knowledge about the Aztec civilization, ensuring that the grandeur of Tenochtitlan is not forgotten (Bernal, 1963).

Mystical Tenochtitlan, Surreal Woodblock Print

Conclusion

The 1524 map of Tenochtitlan stands as a powerful testament to the complexities and contradictions that defined the encounter between the Old and New Worlds. It is a poignant reminder of the vibrant civilizations that thrived in pre-Columbian Americas, yet also a symbol of the violence and cultural upheaval that accompanied the European conquest.

Through this map, we glimpse not only the physical splendor of the Aztec capital but also the profound ingenuity, symbolic richness, cultural resilience, and ecological adaptations of its inhabitants. As we gaze upon the intricate details of Tenochtitlan's layout, we are reminded that beneath the bustling streets of modern Mexico City lies a palimpsest of histories, each layer contributing to the multifaceted tapestry that defines the nation's identity.

In the end, the legacy of Tenochtitlan transcends its physical remnants; it endures as a testament to the human capacity for ingenuity, adaptability, and the indomitable spirit that allows civilizations to rise, fall, and ultimately, leave an indelible mark on the world. By studying the Aztec capital through a multidisciplinary lens, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of human achievement and the enduring power of cultural exchange, even in the face of conflict and conquest.

Mexican Woman Poses wearing Traditional Shamanic Costume with Native Wildflowers

Awaken to the Wisdom of the Ancients

In the echoes of ancient civilizations, we hear the call to awaken - a summons to rediscover our profound connection to the natural world, to honor the cyclical rhythms that govern all life, and to reignite the flame of wonder and reverence that burns within the human spirit.

Let us be your guides on this transcendent odyssey, where the boundaries between the physical and spiritual dissolve, and the echoes of ancient civilizations whisper the secrets of a life lived in harmony with the rhythms of the universe. Embrace the call to awaken, and together, we shall celebrate the majesty of our world and reignite the sacred flames that have illuminated the path of human evolution since time immemorial.

Awaken to the wisdom of the ancients, and let the magic of life flow through you once more.

Aztec Princess Poses with Native Wildflowers of Mexico

Aztec Priestess Poses with Native Wildflowers

References

Aguilar-Moreno, M. (2006). Handbook to life in the Aztec world. Oxford University Press.

Armillas, P. (1971). Gardens on swamps. Science, 174(4010), 653-661.

Aveni, A. F. (2001). Skywatchers: A revised and updated version of Skywatchers of ancient Mexico. University of Texas Press.

Berdan, F. F. (1976). Comerciantes, mercados y el imperio azteca. Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Bernal, I. (1963). Introduction to the archaeological work in Mexico in the field of archaeology. University of Florida Monographs: Social Sciences, No. 24.

Brundage, B. C. (1979). The fifth sun: Ancient Mexican myths and legends. University of Texas Press.

Calnek, E. E. (1972). Settlement pattern and chinampa agriculture at Tenochtitlan. American Antiquity, 37(1), 104-115.

Calnek, E. E. (1976). The internal structure of Tenochtitlan. In E. R. Wolf (Ed.), The Valley of Mexico: Studies in pre-Hispanic ecology and society (pp. 287-302). University of New Mexico Press.

Carrasco, D. (1999). City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the role of violence in civilization. Beacon Press.

Carrasco, D. (2000). City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the role of violence in civilization. Beacon Press.

Coe, M. D. (1964). The chinampas of Mexico. Scientific American, 211(1), 90-99.

Díaz del Castillo, B. (1908). The true history of the conquest of New Spain (A. P. Maudsley, Trans.). Hakluyt Society.

Kubler, G. (1948). Mexican architecture of the sixteenth century. Yale University Press.

Lara, J. (2008). City, temple, stage: Escenographic prehispanic and colonial practices. University of New Mexico Press.

León-Portilla, M. (1962). The Broken Spears: The Aztec accounts of the conquest of Mexico. Beacon Press.

León-Portilla, M. (1963). Aztec thought and culture: A study of the ancient Nahuatl mind. University of Oklahoma Press.

León-Portilla, M. (1987). Aztec Mexico: Origins, rise and fall of the Aztec nation. Nihon Bashi.

Matos Moctezuma, E. (1988). The great temple of the Aztecs: Treasures of Tenochtitlan. Thames & Hudson.

Muñoz Camargo, D. (1892). Historia de Tlaxcala. Oficina tip. de la Secretaría de Fomento.

Mundy, B. E. (1996). The mapping of New Spain: Indigenous cartography and the maps of the relaciones geográficas. University of Chicago Press.

Palerm, A. (1973). The classic period of cultural development: The Mesoamerican cultural core. In K. V. Flannery (Ed.), The Cloud People: Divergent evolution of the Zapotec and Mixtec civilizations (pp. 227-234). Academic Press.

Robertson, D. (1994). Mexican manuscript painting of the early colonial period: The Metropolitan schools. University of Oklahoma Press.

Rojas, J. L. (1986). A record of some things Mexican and Mexican antiquities that are noteworthy, extracted from the codices of 1548 and 1572. In Codex Ramirez (pp. 35-50). University of Oklahoma Press.

Sahagún, B. (1950-1982). Florentine codex: General history of the things of New Spain (A. J. O. Anderson & C. E. Dibble, Trans.). University of Utah Press.

Sanders, W. T. (1976). The agricultural history of the Basin of Mexico. In E. R. Wolf (Ed.), The Valley of Mexico: Studies in pre-Hispanic ecology and society (pp. 101-159). University of New Mexico Press.

Smith, M. E. (2003). The Aztec empire and the Mesoamerican world system. In M. E. Smith & F. F. Berdan (Eds.), The Postclassic Mesoamerican world (pp. 93-107). University of Utah Press.

Šprajc, I., & Sánchez, M. (2012). Astronomía y paisaje arqueoastronómico en Mesoamérica. In A. M. Baéz-Jorge & A. De León (Eds.), Las ciencias en la vida de los Mayas (pp. 123-166). Centro de Estudios Mayas, IIFL, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Townsend, R. F. (2000). The Aztecs (Rev. ed.). Thames & Hudson.

Townsend, R. F. (2009). The Aztecs (3rd ed.). Thames & Hudson.

Jaguar Priestess of the Ancient Aztec Empire

Aztec Priestess in Mystical Tenochtitlan, Surreal Vaporwave

Jaguar Priestess of the Ancient Aztec Empire

Mystic Vistas of Ancient Tenochtitlan