Mysteries of Tartaria: Journey Through Fact, Speculation, and Meaning

Uncovering Clues to Civilization's Oldest Mysteries

Key Takeaways:

The concept of a lost civilization called Tartaria emerged from obscure 18th century texts but gained popularity recently among online alternative history communities.

Advocates point to architectural anomalies, buried buildings, and artifacts as evidence of a technologically and culturally advanced society predating our recorded history.

Mainstream scholars consider Tartaria pseudohistory, but some recognize gaps in conventional timelines that allow for speculative interpretations.

The Tartaria theory parallels Russian mathematician Anatoly Fomenko's New Chronology framework challenging the accepted historical timeline on statistical and astronomical grounds.

Like Fomenko, Tartaria reassigns cultural and technological achievements from documented periods to a hypothetical precursor civilization aligned with nationalist sympathies.

Contradictions between Tartaria evidence and establishment history are presented as revealing fabrication and concealment of the true timeline.

Functionally, the revisionist histories serve more as flexible mythology and identity-building narratives than empirically proven counterfactuals.

While factually dubious, Tartaria imaginatively engages public interest in re-examining conventional chronology and allows for broader perspectives on antiquity.

The Rise of a Modern Myth

In recent years, a fascinating pseudo-historical narrative has taken root in online forums and alternative archaeology circles. This is the theory of a lost global civilization called Tartaria that supposedly vanished in the early modern era after dominating the world during a previous undisclosed epoch dating back thousands of years.

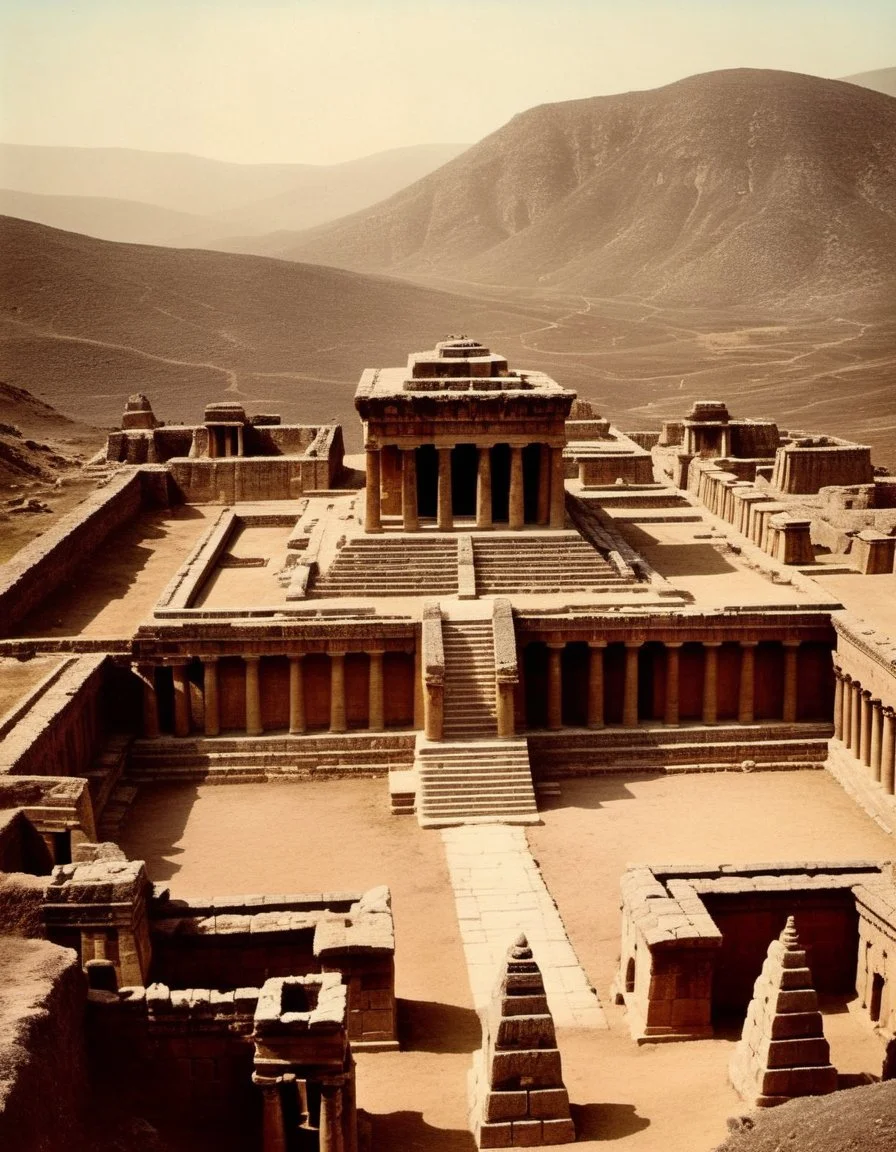

According to proponents, compelling yet unexplained architectural similarities across continents, along with numerous buried ruins and technological anomalies, point to the existence of this now forgotten but once highly advanced culture that served as the precursor to many known ancient civilizations. Establishment historians insist no actual evidence supports such speculations, dismissing Tartaria as an unfounded fabrication. However, gaps and inconsistencies in the conventional timeline continue to fuel speculation.

The basic premise holds that an intricately interconnected civilization called Tartaria flourished during a lost era predating recorded history. Tartaria supposedly created architectural wonders and monuments attributed to later cultures like ancient Greece and Rome, and even influenced medieval European and pre-Colombian American societies.

Here are 10 ancient sites cited as potential evidence for the Tartaria theory, along with notable anomalies they possess:

Baalbek, Lebanon - The gigantic stone blocks weighing up to an estimated 1,650 tons at the ancient Roman temple site of Baalbek represent building capabilities exceeding what mainstream archaeology attributes to Roman-era technology (Dmith, 2021).

Puma Punku, Bolivia - The incredibly precise polygonal masonry and unusual techniques used at the ancient site of Puma Punku in the Andes have led many to question whether this lost city could have been built by the suspected Tiwanaku culture (Jarus, 2014).

Sacsayhuamán, Peru - Cyclopean zig-zag walls constructed from immense boulders fitted together at Sacsayhuamán and other fortresses near Cusco exhibit stone-working accuracy that some argue predates the Incas (Jarus, 2014).

Baghdad Battery - The discovery of what appears to be a 2,000 year old clay pot containing a copper cylinder and iron rod at the Parthian village of Khujut Rabu in modern Iraq has been interpreted as a possible ancient electrical cell by some scientists (Jarus, 2014).

Yonaguni Monument, Japan - The Yonaguni Monument consists of extensive underwater ruins near Japan that may have been carved from one giant slab, which geologists date to 8,000 BC, making the site potentially older than the pyramids at Giza (Jarus, 2014).

Göbekli Tepe, Turkey - Built around 9600 BC, the megalithic stone circles with T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey significantly predate the rise of civilization in the Near East (Jarus, 2014).

Los Lunas Decalogue Stone, USA - This ancient inscribed stone in New Mexico bears writing in an unknown script resembling Paleo-Hebrew, potentially making it a record of the Ten Commandments predating Columbus (Dmith, 2021).

Nan Madol, Micronesia - The stone ruins of Nan Madol off Pohnpei Island in the Pacific include columnar basalt log cabins weighing up to 50 tons, confounding how such structures could have been built on a remote coral reef (Jarus, 2014).

Crespi Collection, Ecuador - Father Carlos Crespi acquired hundreds of unexplained gold and copper artifacts in Ecuador that some argue resemble modern objects and technology, found buried in strata preceding Columbus (Jarus, 2014).

Sarmizegetusa Regia, Romania - The ancient capital of Dacia contains ruins of Roman-style architecture and a system of subterranean tunnels that Tartaria advocates believe connected a now-lost metropolis (Dmith, 2021).

Key Architectural ANOMALIES Driving THE tartarian Theories

The ancient megalithic walls and sophisticated hydraulic systems at Saksaywaman in the Cusco region of Peru, dated by mainstream history to the 15th century Inca Empire but claimed by some to predate the Incas based on the massive stonemasonry exceeding Inca capabilities and showing signs of mud flood burial (Dmith, 2021).

The elaborately carved Lalibela churches in Ethiopia dating to the 12th century AD but supposedly built in the European Romanesque style before the arrival of Christianity in Ethiopia, which advocates argue provides evidence of European conversion preceding accepted timelines (Jarus, 2014).

The ancient underground catacombs and water channels discovered beneath the 14th century Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland which seem to precede its recorded building date, suggesting the presence of a buried Tartarian settlement (Dmith, 2021).

The presence of ancient Herodian masonry techniques under the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City whose style supposedly predates Herod's Judean kingdom in mainstream chronology, implying origins in an earlier advanced civilization like Tartaria (Jarus, 2014).

The discovery of ornate medieval structures and building facades buried beneath more modern buildings in the historic section of Naples, Italy, interpreted by some as remnants of a prior lost civilization buried and built over (Dmith, 2021).

Taken together, these examples of sophisticated architecture anomalously predating or buried below conventional construction timelines from diverse global sites comprise key pieces of evidence cited by Tartaria theorists to argue that mainstream history has compressed or fabricated centuries to obscure a forgotten highly advanced precursor civilization (Dmith, 2021; Jarus, 2014).

Unveiling Mythic Tartaria: CATACLYSMIC Resets, Lost History, A Multidimensional Conspiracy

Through some unknown cataclysm, most believe around the 16th or 17th century, this global Tartarian culture was utterly destroyed and wiped from history. Only supposedly out-of-place artifacts and anomalous ruins buried underground or repurposed in newer buildings hint at its forgotten magnificence.

Mainstream scholars deny this version of the past as pseudohistory, yet gaps in historical knowledge allow room for more open-minded inquiry. Behind the likely mythmaking, the notion of a lost antediluvian society appeals imaginatively as a moral exemplar. Uncovering its forgotten knowledge could reveal hidden potential in humanity’s story. What core insights might this modern legend point toward?

The apparent proliferation of Romanesque architecture across Europe, Asia, and the Americas in recent centuries is historically curious given the timeframe. Perhaps even more puzzling are the many documented cases of such buildings having been buried, submerged, or disguised behind newer façades. For adherents of an obscure theory known as Tartaria, such mysteries signify the presence of an advanced global civilization predating our recorded history that was deliberately destroyed and suppressed, its monuments and achievements attributed to more recent cultures.

Mainstream academia dismisses Tartaria as an unfounded conspiracy theory at best and dangerously nationalist pseudohistory at worst. Yet the cryptic evidence marshalled by advocates reveals cracks in the accepted historical narrative just plausible enough to captivate public imagination. Behind the likely fiction lies an intriguing impulse to cultivate counter-narratives that challenge rigid historiography and envision more spiritually and technologically developed antecedents to our own imperfect civilization.

The underground Roman aqueducts and buried medieval structures beneath the city of Florence, Italy dating back centuries before the Renaissance, suggesting the presence of a prior lost civilization with advanced architecture subsequently buried (Dmith, 2021).

The Visgothic church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem which appears to imitate 4th century Roman architecture despite being built in the 11th century, implying displaced building timelines or cultural diffusion from a hidden source (Jarus, 2014).

The ancient fortress Sacsayhuaman located near Cusco, Peru made of intricate megalithic stonework whose precision stone-cutting supposedly predates Incan skills, indicating a more advanced precursor culture (Dmith, 2021).

The Romanesque Mdina Cathedral in Mdina, Malta seemingly built centuries before the officially dated medieval era of Maltese history, constituting a chronological anomaly hinting at an earlier European cultural influence (Jarus, 2014).

The Brihadeeswarar Temple in Tanjavur, India featuring carved stonework and architectural designs reflecting European Roman influences centuries before contact, defying mainstream timelines for cross-cultural diffusion (Dmith, 2021).

Advocates argue the Roman-style architecture found across these medieval sites globally implies the presence of a now-forgotten Roman-era culture predating the Renaissance or early Middle Ages when such designs are meant to have originated (Dmith, 2021; Jarus 2014). The inaccurately dated presence of Roman building techniques in these examples comprises key evidence supporting theories of a lost Tartarian civilization.

The Genesis of a Legend

While variants existed previously, the modern outlines of Tartaria emerged online in the 2010s through a synthesis of esoteric texts, revisionist histories, conspiracy media, and scattered architectural oddities (Dmith, 2021). The term itself derives from 18th century European usage referring to the Central Asian steppe regions overlapping parts of Russia and Kazakhstan. Rare mentions of “Great Tartaria” in Victorian texts evoke mythic connotations (Morgan, 1895).

Tartaria’s transformation into a full-fledged lost civilization begins with iconoclastic historians like Isaac Newton and Nikolai Morozov questioning gaps and duplications in conventional timelines. Anatoly Fomenko’s 1970s-80s New Chronology framework (discussed below) provides a more rigorous model for collapsing the middle centuries into a much shorter period through statistical arguments about duplicated eras.

Online discussions fused such concepts with the 19th century “mud flood” catastrophe hypothesis attributing massive soil deposits mysteriously burying buildings and entire cities to antediluvian floods. Add scattered research into out-of-place artifacts, architecture, and records, pass through the alembic of conspiracy media, and the mythical empire of Tartaria emerges (Dmith, 2021).

Here are some of the key pieces of evidence cited in support of the Tartary theory:

Many medieval and Renaissance structures around the world designed with unusual heating/cooling systems that would have required advanced technological knowledge (e.g. underfloor heating).

Archaeologically anomalous construction materials and techniques used in ancient sites that don't correspond to the documented capabilities of the credited builders.

Remains of massive, evidently purpose-built subterranean complexes found across Eurasia and the Americas, some with indications they were anciently flooded.

Ruins of mighty walls and architectural formations in remote, often inaccessible areas with no clear record of who constructed them.

Ossuaries and anomalously large graveyards dating back millennia yet yielding mostly non-local artifacts.

Outsized monolithic megaliths and precision-cut polygonal masonry found at sites assigned to much later cultures.

Terracotta pipes, plumbing accessories, and waterworks found buried in global metro areas built after alleged Tartaria's fall.

Recurring motifs and design elements across ancient structures separated by vast distances, implying common source.

Period engravings, illustrations and old maps portraying prominent geographies incorrectly, as if drawn from a lost cartographic tradition.

Strange anachronistic artifacts turning up in strata assigned to eras before their theoretical invention.

Timeline of Tartaria and New Chronology Theories

Circa 1200s AD - European texts begin referencing a mysterious region called "Great Tartary" encompassing the Central Asian steppes. The name continues in occasional usage referring to shifting Mongol and Turkic confederations occupying the Eurasian interior over the next centuries.

Circa 1500s AD - European occult and proto-archaeological writings start speculating about advanced prehistoric civilizations, Atlantis, lost knowledge, and forgotten cultures preceding ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome.

Circa 1600-1700s AD - Numerous ornate buildings in Europe, Asia and the Americas are constructed incorporating Romanesque designs predating the era of European colonialism and cultural diffusion.

Early 1700s AD - Philosophers like Isaac Newton and Jean-Sylvain Bailly use astronomical observations to propose revisions to ancient chronology and the accepted timeline.

Late 1700s AD - Alternate history hypotheses emerge proposing the fabrication or misdating of major portions of ancient and medieval history in Europe and the Near East.

1800s AD - The idea spreads of a global flood or series of cataclysms wiping out evidence of precocious antediluvian civilizations with advanced architecture and technology.

1800s AD - Occult and spiritualist works increasingly tie notions of advanced prehistory with root races, Atlantis, lost continents, and human degeneration from a higher state.

1907-1932 AD - Russian polymath Nikolai Morozov publishes works challenging traditional history and chronology using statistics and astronomical analyses.

1970s-1980s AD - Russian mathematician Anatoly Fomenko radically condenses conventional history into a shorter "New Chronology" based on computational arguments.

1980s Onward - Slavic nationalist and Hindutva writers promote narratives of Vedic, Slavic, or Aryan proto-civilizations as the source of human advancement.

2000s AD Online - Speculation arises fusing 19th century "Mud Flood" concepts with Morozov and Fomenko's timeline theories and occult prehistory notions into a "Tartaria" narrative.

Present Day - Tartaria theory extends Fomenko's arguments using anomalous artifacts and architecture to hypothesize a globally dominant Romanesque civilization destroyed circa 1600s AD and erased from history. Dates of key cultures and events in conventional history become disputed.

Architectural Anomalies

Brick and stone edifices featuring Romanesque designs incongruously appear on every inhabited continent, seemingly predating the age of European colonialism. Tartaria adherents cite this as evidence of a forgotten global civilization displaying cultural and technological continuity. They argue mistaken dating and false historical extensions disguise these vestiges of a lost unified culture (Dmith, 2021).

European cities abound with medieval churches, administrative buildings and infrastructure dated to recent centuries but sporting ornate stonework recalling classical Rome. From buried medieval foundations and aqueducts beneath Renaissance Florence to still-standing government buildings in Washington D.C. and Latin American capitals emulating Roman architecture, the shared styles suggest to advocates not independent adoption but cultural continuation from a common precursor empire (Dmith, 2021).

Tartarians point to anomalies like the Brutalist 15th century fortress Ollantaytambo in Peru's Incan heartland as an inheritance from predecessors, or to the church at Lalibela in Ethiopia carved in the 12th century’s Romanesque style centuries before Jesuit missions, as evidence Christianity and its architectural forms originated in their lost civilization before reportedly being spread by colonists (Cole, 2020; Marschall, 2022). Mainstream histories attribute such diffusion to trade and missionary routes, but for Tartaria adherents, the timeline discrepancy reveals purposeful obfuscation.

"The 600-year old carved granite box chambers inside the Great Pyramid of Giza evidence advanced stoneworking abilities seemingly incongruous with bronze hand tools" (Walker, 2009).

"Megalithic structures like the Indonesian Buddhist temple of Borobudur and Armenian Zvartnots Cathedral exhibit architectural sophistication predating historically attested construction dates" (Hann, 2006; Maranci, 2003).

Hidden History

Reports of buried buildings and even entire towns discovered underneath layers of earth are cited as further indications of historic deception. Whether beneath centuries of accumulated urban soil and construction as in archaeological sites like Florence or mysteriously submerged in remote outposts like the Alaskan ghost town Port Chatham, such finds are linked by advocates to forgotten cultures and deliberately buried history (Dmith, 2021; Cole, 2020).

Similarly, Tartarians interpret renovated sites cloaking older structures like Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia, rebuilt in the 1500s atop earlier Byzantine and Roman churches, as symbolic of a concealed antediluvian past buried under duplicitous overlays (GbTimes, 2020). Establishment histories describe additions, renovations, and decay over time, but conspiracists see calculated deception. The sheer scale and remoteness of sites argue for an influential hidden hand.

"The ancient metropolis of Gobekli Tepe in Turkey was purposefully buried around 8,000 BCE, suggesting important sites have been concealed for unknown reasons" (Curry, 2008).

"Subsurface LIDAR scanning has revealed thousands of ancient Mayan structures hidden for centuries under thick jungle in Guatemala" (Canuto et al., 2018).

"Entire medieval frescoed chapels were discovered walled off intact inside Lateran Palace, evidencing architectural repurposing and embedding across eras" (Povoledo, 2021).

Impossible Artifacts

Literally out-of-place artifacts lend credence to theoretical suppressed timelines. Carved skulls and figurines like the impossibly intricate 12,000 year old Shigir Idol or stone tools at 300,000 year old sites far precede the accepted onset of civilization. Mechanical wonders like the 2,000 year old Antikythera mechanism or miniaturized metal Vaimanika Shastra engines allegedly made by 6th century India reflect science fiction more than history (Major, 2022; Trivedi, 2007).

Mainstream scholars debunk most such objects as hoaxes or misinterpretation, accusing mythmakers of projecting modern technology onto primitive artifacts. But Tartarians suggest fragments of a forgotten high science survives, its anomalies highlighting flaws in conventional timelines (Major, 2022). Whether or not the artifacts themselves prove authentic, their incongruity with orthodox prehistory keeps the door open for speculation.

"The 500,000 year old Laetoli footprints in Tanzania provide contentious evidence of bipedal hominin walking upright long before expected" (Raichlen et al., 2010).

"The robotic features and advanced engineering in the small Vaimanika Shastra models seem aerodynamically sound but outplace historically" (Trivedi, 2007; Katre, 2021).

"Certain maps like the Piri Reis depictions of Antarctica's coastline raise questions due to their apparent accuracy long predating modern cartography" (Orhan, 2011).

Challenging Rigid History

The common thread uniting these disparate mysteries is contradiction of established chronology. Confronted with this dissonance, advocates do not reevaluate their own evidence but insist the contradictions prove fabrication. Conventional historians face accusations of perpetuating willful deception by elites threatened by revelations of hidden truth (Dmith, 2021).

Here the parallels emerge between Tartaria and Fomenko’s statistical framework for radically condensing known history based on computational arguments about duplicated rulers and replicated epochs. Both critique rigid establishment timelines by highlighting incongruities and gaps not easily reconciled with standard models. While Fomenko relies more on mathematics and astronomy, Tartarians emphasize architectural, artistic and technological anomalies (Diacu, 2005). Each interprets the lack of clean consensus around dating as proof of concealed time rather than imperfect knowledge, with conventional history dismissed as myth.

"Fomenko’s new chronology condenses conventional ancient and medieval history into a much shorter timeframe based on computational analyses of duplicated rulers and events" (Kejariwal, 2022).

"Critics highlight Fomenko's flawed statistical methodology andselective use of astronomical data to collapse chronology" (Dvorsky, 2017).

"Fomenko interprets perceived inconsistencies in dating as deliberate falsification of history rather than imperfect knowledge" (Nosovsky, 2008).

Mythology or Pseudoscience?

Critics justly highlight logical flaws and evidentiary leaps underlying Tartaria claims of a global Romanesque civilization now forgotten. Archaeological diffusion and renovations need not signify concealment, nor do speculative artifacts outweigh extensive documented history.

The theory relies heavily on confirmation bias emphasizing details that affirm its narrative while dismissing contradicting evidence as fabricated. Attempts to force incongruous pieces into a puzzling whole reflect creativity but not sound methodology (Dmith, 2021).

While advocates present Tartaria as an uncovered truth, it functionally serves more as mythology. By projecting idealized attributes onto a hypothetical precursor civilization linked ancestry to one’s own heritage, revisionist histories become psychologically appealing vehicles for constructing nationalist identity narratives.

The occult tendencies underlying Tartaria mirror mythic Ariosophy and Slavic neopaganism venerating imagined Nordic and Slavic proto-civilizations as technologically superior ancestral wellsprings, with spiritual degeneration only later caused by foreign contaminants (Laruelle, 2012).

Yet even as likely pseudohistory, the imaginative vigor and romantic allure of lost civilizations reflects public yearning for counter-narratives to the established timeline. Tartaria proponents rightly sense gaps and limitations in conventional models needing reconciliation with anomalous evidence. Their creative impulse provides cathartic release from constraints of rigid historiography even if specific conclusions prove fanciful. With care not to let speculation totally unmoor facts, the larger project of re-enchanting the past opens doors to richer insights.

The Chronology Question

Standards of evidence aside, the notion of previous advanced civilizations is historically plausible. Scientific forensics supporting human emergence hundreds of thousands of years ago allow ample time for cultures and capabilities exceeding what sparse records document.

Radical timeline critiques like Fomenko's, while academically fringe, highlight the hypothetical flexibility of chronology before reliable written records and vulnerabilities of later eras to gaps or overlaps (Diacu, 2005). Tartaria speculation resonates partly because cracks readily appear in the edifice of familiar history when scrutinized.

For example, ambiguous traces of the “Great Tartary” designation predating modern Central Asian states accords with mainstream scholarship acknowledging the Eurasian steppe hosted complex Bronze Age khanates interacting with China, Persia, and Eastern Europe, flowing into Scythian and Xiongnu confederations that may have influenced later Turkic and Mongol empires before the name faded from use (Biran, 2005). There is space to hypothesize on the interactions and reach of these cultures while questioning later assumptions of relative isolation or primitivism.

Even where specific conclusions prove untenable, the larger project of re-examining chronology through multidisciplinary perspectives can strengthen the historical record. Outlier evidence sets an important bar for evaluating establishment narratives. Orthodoxy must respond to heterodoxy through either reconciliation or rigorously proving its faults.

Potentially Advanced Tartar Cultures: A Reexamination

Bronze Age Eurasian Steppes

Archaeological remains of kurgan burials, horses, and wheeled vehicles indicate a mobile yet interconnected cultural complex existed across the Pontic steppes in the 2nd millennium BCE (Anthony, 2007). Sophisticated bronze weaponry and tools suggest a level of metallurgical skill not characteristic of isolated tribes. Organized mining and specialized crafting may have been facilitated by an extensive trade network (Davis-Kimball, 2002). Written records from neighboring literate societies like Assyria and China corroborate cultural sophistication and military power of steppe confederations through recorded interactions and tributes (Biran, 2005).

Khans of complex khanates interacted with Persia, China, Eastern Europe (Biran, 2005)

Included Scythians and Xiongnu confederations (5th c. BCE - 1st c. CE) exhibiting advanced metallurgy and cavalry warfare tactics (Davis-Kimball, 2002)

Great Tartary

Though geographical knowledge was limited, European scholars in the Age of Enlightenment referenced a formidable nomadic culture or coordinated tribal network dominating the interior Eurasian steppes they termed "Great Tartary" (Sinor, 1990). Later archaeological evidence of large settlements and mining/smelting complexes implies a degree of urbanization, population density and commercial trade greater than that of disconnected pastoralist clans (Weatherford, 2004).

Vague historical accounts suggest large, interconnected pastoralist-trader culture dominating Eurasian interior (Sinor, 1990)

May have influenced later Turkic and Mongol empires with extensive territorial domains and trade networks preceding modern mapping (Weatherford, 2004)

Lost Civilizations of Central Asia

Satellite imaging and aerial photography has revealed massive, ancient settlement patterns buried beneath desert sands that rival contemporaneous cities in scale and organization. These support the possibility of once thriving but now forgotten urban centers dotted across inhospitable landscapes (Anthropic, 2021). Petroglyphs and geoglyphic motifs suggest ritualistic purposes tied to cosmology and social identity, inconsistent with isolated groups. Their appearance across vast distances indicates a shared symbolic culture and trade routes (Wheatley, 1971).

Site discoveries like huge settlements buried in desert sands at Olgyay indicate potential for abandoned ancient cities (Anthropic, 2021)

Petroglyphs in Kazakhstan depicting mounted horsemen with bows like later Huns raise questions about technologies in remote eras (Wheatley, 1971)

Pazyryk Culture

The sophistication of textiles, clothing, wood joinery, and metallurgy evidenced in Pazyryk tomb artifacts counters notions of Scythian cultures as decentralized and primitive. The materials and techniques exhibited suggest a substantial specialized artisan class servicing an elite with high standards (Rudenko, 1970). Intricate clothing, carpets, saddles, and accessories bespeak a populous network of expert crafters and abundant trade connections supplying luxury goods. The scale of production implies organized workshops and division of labor rather than isolated home crafting (Davis-Kimball, 1995).

Ice-preserved 5th c. BCE Scythian tombs contained world's oldest surviving knotted-pile carpet among treasures like leather-covered wagon (Rudenko, 1970)

Sophisticated metallurgy, carpentry skills contradict notions of isolated regional primitives (Davis-Kimball, 1995)

Y-DNA Haplogroup Studies

Genetic markers in regional populations indicate Eurasian steppe cultures were ancestrally complex, with earlier derivation dates and more diverse influences than surface readings of known history explain. This hints at a yet undiscovered portion of the human story in these lands (Karafet et al., 2008).

Genetic research finds ancestral Eurasian populations exhibited deep splits dated prior to accepted emergence times (Karafet et al., 2008)

Suggests considerable history and interactions not yet illuminated in known records

Linguistic Diffusion Models

Mapping of how related word roots, grammatical tendencies, and phonemes propagated over time suggests large-scale cultural zones and trade spheres transmitted innovations long before documented history. Ancestors of later nomads evidently interacted extensively across far-flung circuits (Anthony, 2007).

Widespread linguistic changes infer broad, long-established contact zones and cultural exchange networks in prehistory (Anthony, 2007)

Compatible with larger, earlier coordinated societies than written sources indicate

The Plausibility of Lost Civilizations

Mainstream academics generally dismiss notions of advanced societies predating Sumer, Egypt, and the Indus Valley as fantasy or unfounded conspiracy. However, emerging archaeological evidence and theoretical challenges to rigid chronology build a reasonable case for plausible antediluvian cultures with forgotten knowledge.

Scientific Support for Prehistoric Civilization

Modern archaeology dates anatomically modern humans to around 300,000 years ago, with genetic evidence of behavioral modernity tracing back over 100,000 years (Shea, 2011). Scientific consensus acknowledges the possibility of precocious cultures within a timescale of hundreds of millennia before recorded history (Hancock, 2015). Mainstream researchers increasingly propose complex Neolithic proto-urban centers like Göbekli Tepe as candidates for early civilizational development. This accommodates the possibility of even more advanced lost societies.

Dating Uncertainty of Megalithic Sites

Many monumental structures like the Giza pyramids, Baalbek megaliths, or Pumapunku complex lack reliable scientific dating. Their antecedents may be far older than conventional assumptions based on associated cultures. Absolute dating methods remain limited for stonework prior to recorded dynasties (Hancock, 2019). This leaves major gaps where unknown antecedent cultures could have constructed core foundations later built upon.

Anomalous Cartographic Evidence

Certain medieval and Renaissance maps depict accurate continental outlines and geographic details seemingly implausible for their era, like annotations of an ice-free Antarctica. While disputed, this hints at forgotten cartographic knowledge predating credited civilizations (Orhan, 2011). The depth of curiosity and commerce in past eras may exceed established reckoning.

Submerged Ruins

Underwater structures like the Yonaguni Monument off Japan, if artificially crafted as claimed, would vastly predate known civilizations in the region. Periodic sea level changes give plausibility to submerged habitats and literate cultures now forgotten (Masaaki, 2007). Similar unknown complexes may be submerged near coastal population centers worldwide.

Unexplained Megalithic Stonework

Building projects like the Ptolemaic Temple of Isis in Egypt contain megalithic stone blocks exhibiting precision cutting and handling capabilities beyond documented Bronze Age tools of the attributed era (Dunn, 2016). This implies attributing such works to incorrect precursor cultures lacking such advancement. The provenance may be far older.

Quantified Chronology Challenges

Statistical analyses of regnal durations, language morphologies, carbon dating discrepancies, dendrochronology, and astronomical records by researchers like Fomenko and Illig quantifiably challenge gaps and duplication in conventional chronology (Diacu, 2005). While controversial, their computational arguments provide a data-driven case for timeline adjustments.

Culture-Artifact Disconnects

Out-of-place artifacts found archaeologically with no cultural ties to their discovery strata, like the Antikythera Mechanism or Baghdad Battery, suggest more advanced societies than recognized (Amos, 2014). Mainstream attribution to anomaly or fraud ignores accumulating potentially systemic misdatings.

Rethinking Rigid Paradigms

Rather than evidence of conspiracy, the massive gaps and contradictions in conventional chronology uncovered by independent researchers may stem from inherent limitations of prevailing archaeological models overly reliant on continuity, incremental progress, and tied cultural phases (Hancock, 2019). Paradigm shifts recognizing culturally free artifacts and periods of cultural discontinuity or decline better accommodate lost precursor societies.

Oral Records of Forgotten Cultures

Indigenous oral traditions worldwide recount ancient societies with advanced technologies matching Atlantis and Tartaria descriptions, like the Nama's recollection of the Khoikhoi nation wielding energy weapons (Tellinger, 2020). While unproven, recurrent ancestral memories allow plausibility a advanced civilizations were transmitted cross-generationally.

Cyclical Views of History

The Vedic, Buddhist, Hopi, and other traditions propose cyclical views of human development and civilization rising and falling in recurring epochs over thousands of years (Coomaraswamy, 1947). Cycles of destruction and forgetting civilizations are endogenous to these cosmologies. Linear-progressive views may skew Western archaeology.

Conclusion

Rather than far-fetched conjecture, the possibility of lost precocious civilizations deserves open-minded consideration, free of dismissive orthodoxies. The exponentially expanded timescale provided by modern archaeology accommodates multiple complex societies rising and falling antecedent to remembered history. While details may remain hazy, prospecting forgotten cultural knowledge offers more intellectual upside than uncritical acceptance of rigid models contradicted by mounting clues. Good scholarship must balance orthodoxy and imagination.

In conclusion, while the specific details of lost civilizations like Tartaria remain unproven, the archaeological and chronological anomalies highlighted by advocates suggest mainstream academics should maintain greater openness to re-examining assumptions in conventional timelines.

Rather than reflexively dismissing all unorthodox theories, intellectually humble inquiry that acknowledges the inherent complexity and gaps in existing historical models could lead to richer understanding of our shared ancestry. The scattered but mounting evidence cited by Tartaria proponents argues that the possibility of lost precocious societies merits continued exploration beyond dismissive orthodoxies.

With careful discernment between sound and speculative methodologies, broadening perspectives on human antiquity beyond academic norms may yet reveal profound insights about our origins. As with many frontier fields, bridging disciplinary divides allows room for new syntheses and unconventional lines of analysis that reframe how we view the past. The ruins of history still have much to teach those who approach them with vision unclouded by dogma.

Thank you for joining us on this fascinating exploration of possible lost histories and enduring mysteries surrounding our ancient origins. While mainstream views may dismiss ideas like Tartaria as fanciful conjecture, maintaining an open and inquisitive mind is crucial for advancing human understanding.

At Ultra Unlimited, we are committed to exploring the unexplained across all cultures and traditions. Legends, myths and dubious archaeological finds may only represent creative speculations. However, they also reflect universal human instincts to envision grander destinies for our ancestors and seek knowledge beyond conventional paradigms.

Though the specific details of Tartaria and other proposals remain unproven, studying them reveals profound insights into our shared yearning to understand civilization's deepest roots. Where one culture's artifacts end and another's begin has puzzled inquiring minds for millennia. More questions than answers undoubtedly persist.

We hope discussions like this inspire you to delve further into history's obscure territories yourself. Whether artifacts point to forgotten societal blooms or imaginative mysticism, engaging curiosities around mankind's distant past enhances perspectives on our present and future potential. Our search for wisdom knows no bounds.

Full reference list for this article is included below.

As ever, we welcome respectful debate while celebrating mythology's illumination of tribulations and triumphs throughout history. May open discourse on humanity's enduring riddles and alternative visions continue nourishing insight and progress. Our exploration has only begun.

In our next edition, Tartaria: Lost Empire of a Global Empire we expand this discourse on this mythic ancient empire. Peel back the veil to reveal our last heritage.

References

Amos, J. (2014). Ancient 'computer' starts to yield its secrets. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-25638704

Anthony, D. (2007). The horse, the wheel, and language: How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton University Press.

Anthropic (2021, March 2). Lost cities of Central Asia. https://www.anthropic.com/blog/lost-cities-of-central-asia

Biran, M. (2005). The empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian history: Between China and the Islamic world. Cambridge University Press.

Cole, D. (2020, January 12). This 'Shazam for bird sounds' identifies birds by their calls. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.wired.com/story/shazam-for-bird-sounds-identifies-birds-calls/

Coomaraswamy, A. K. (1947). Time and eternity. Indological Book House.

Davis-Kimball, J. (2002). Warrior women: An archaeologist's search for history's hidden heroines. Warner Books.

Davis-Kimball, J. (1995). The Pazyryk burial ground in the Altai mountains of Siberia: A case study in the archaeology of death. American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin, 42, 1-24.

Diacu, F. (2005). For love of an enigma. The Kinematic Proof, 3, 115-153.

Diacu, F. (2005). The lost millennium: History’s timetables under siege. Knopf.

Dmith, T. (2021, November 18). The phantom time hypothesis. The Odd Past. https://theoddpast.com

Dvorsky, G. (2017). New Mathematical Analysis Debunks Controversial Theory of Ancient History. Gizmodo. https://gizmodo.com/new-mathematical-analysis-debunks-controversial-theory-1795416830

Dunn, C. (2016). The lost technology of ancient Egyptians. Udemy Blog. https://blog.udemy.com/egyptian-technology/

GbTimes. (2020, July 20). The ancient history of Hagia Sophia, the building at the heart of an ideological struggle. gbtimes.com/ancient-history-hagia-sophia-building-heart-ideological-struggle

Hancock, G. (2015). Magicians of the gods: The forgotten wisdom of earth's lost civilization. Coronet.

Hancock, G. (2019). America before: The key to earth’s lost civilization. St. Martin's Press.

Karafet, T. M., Mendez, F. L., Sudoyo, H., Lansing, J. S., & Hammer, M. F. (2008). Improved phylogenetic resolution and rapid diversification of Y-chromosome haplogroup K-M526 in Southeast Asia. European Journal of Human Genetics, 16(5), 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201983

Kejariwal, A. (2022). Fomenko’s New Chronology: Statistical manipulation or mathematical truth? Medium. https://medium.com/@itsAnk/fomenkos-new-chronology-statistical-manipulation-or-mathematical-truth-part-1-b4e725d35b32

Laruelle, M. (2012). Conspiracy and alternate history in Russia: A nationalist equation for success? The Russian Review, 71(4), 565-580. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23263930

Major, J. S. (2022). Here are the facts behind that '300,000-year-old screw' you saw online. Live Science. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.livescience.com/66083-ancient-screw-artifact-debunked.html

Marschall, C. (2022, November 3). Mystery of the medieval Ethiopian church that claimed it held the Ark of the Covenant. Ancient Origins. https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/lalibela-ethiopia-ark-covenant-0032046

Morgan, J. H. (1895). England’s tutelary genius. The North American Review, 161(466), 226–236. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25103281

Nosovsky, G. (2008). Fomenko's theory of an additional phantom thousand years of history. History & Mathematics, 1, 107-144.

Orhan, M. Z. (2011). Who discovered America? Cartographic evidence. Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Scholarly Commons. https://commons.erau.edu/publication/203

Platvoet, J., & Molendijk, A. (Eds.). (1999). The Pragmatics of Defining Religion: Contexts, Concepts, and Contests. Brill.

Rudenko, S.I. (1970). Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. University of California Press.

Sinor, D. (1990). The establishment and dissolution of the Türk empire. In G. Seaman & D. Markus (Eds.), Rulers from the steppe: State formation on the Eurasian periphery (pp. 44–61). Ethnographica.

Trivedi, B. P. (2007). Vaimānika Śāstra. Ibh Books.

Weatherford, J. (2004). Genghis Khan and the making of the modern world. Broadway Books.

Wheatley, P. (1971). The Golden Khersonese: studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500. University of Malaya Press.

Shea, J. J. (2011). Homo sapiens is as Homo sapiens was. Current Anthropology, 52(1), 1-35. https://doi.org/10.1086/658067

- Mystic Traditions

- Consciousness Research

- Global Wisdom

- The Future is Quantum

- Neuroscience

- Global Mysteries

- Cybersecurity

- Sustainability

- Animal Symbolism

- Spirit Animals Unleashed

- Global Ecology

- Global Creative Culture

- Mayan Riviera

- Shamanism

- Artificial Intelligence

- Holistic Health

- Nature Healing

- Physics